In 2009, a sea turtle (now known as Seemore) suffered damage to her shell after being struck by a boat. She was sent to live out her life at SEA LIFE Minnesota Aquarium from a turtle hospital in Florida.

But her injury caused what’s called positive buoyancy disorder (or « bubble butt syndrome »), which traps air between her body and shell. It made it hard for her to dive, float and swim.

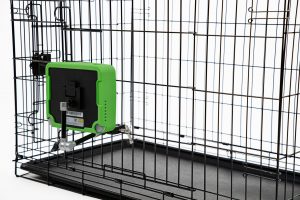

Enter the genius team of undergrads from University of Minnesota who printed a 3-D prosthesis — called an exoshell — to correct Seemore’s buoyancy problem. Today Seemore swims with her 2 pound (0.9 kilogram) « backpack » just like a regular sea turtle.

Seemore’s story is thanks to the miracle of 3-D printing, and it’s becoming more common in veterinary medicine to repair horrifying injuries to animals — both domesticated and wild. These days, veterinarians and wildlife conservationists are following the lead of physicians treating human patients by using 3-D printing to create prosthetics for injuries to animal limbs, fins, beaks, bones and yes, shells.

This technology is being used to create everything from prosthetic legs for kittens and puppies to replacement beaks for toucans. And while off-the-shelf implants and prosthetics are available and can be adapted, often it’s just as simple to create a 3-D implant, part or prosthetic.

Just as in humans, veterinarians use technology — CT scans and MRI — to create images of the animal’s body. The scans provide physicians and conservationists with a 3-D image of what the damaged part looks like and helps them produce an exact representation of what the new part needs to look like. 3-D printing is used for prototyping the damaged part and the replacement.

The image creates a « map » that is uploaded into the computer controlling the printer. Following the map, the printer puts down layer after layer of material until the new part is formed. A variety of materials can be used for 3-D printing, including different types of plastics, ceramic, metals and even living cells.

But just because an animal might seem like a potential candidate for a prosthetic, doesn’t mean it will get one. For example, size matters — very large or very small dogs are more difficult to fit. The residual limb also has to be healthy; the animal also shouldn’t be any issues with gait or range of motion. And believe it or not, animals with prosthetics have to rehab, just like their human counterparts, so they can build up their strength and learn how to use their new limb properly.

Lire la suite: animals.howstuffworks.com