Diagnostic imaging such as X-rays, MRIs, and CT scans are important tools in monitoring the health of humans and animals. But for researchers in the field, it is difficult to administer these common tests on wild populations.

Now, scientists at the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution (WHOI) are working with colleagues at the Cincinnati Zoo & Botanical Garden and other zoos and aquariums to test the use of thermal video and image analysis to measure heart and respiration rates in a variety of animals in a stable setting.

The goal, say researchers, is to use this controlled data to advance the development of non-invasive methods of assessing animal health in the wild, especially threatened and endangered species for which the risks associated with more invasive diagnostic techniques might be prohibitively high.

A new paper detailing their work was published today in the journal BMC Biology.

The ability to measure and monitor an animal’s metabolic rate, or energetic expenditure, provides a window into a species’ reproductive and survival chances. However, it is logistically difficult, and often invasive, to collect these benchmark measurements in wild populations. Even simpler tests such as obtaining heart and respiration rates, often require animals to be immobilized, which comes with risks. Attaching tracking devices can be costly and invasive.

Caroline Rzucidlo, a graduate student in the MIT-WHOI Joint Program in Oceanography/Applied Ocean Science & Engineering, led the study with colleagues including Michelle Shero, an associate scientist at WHOI.

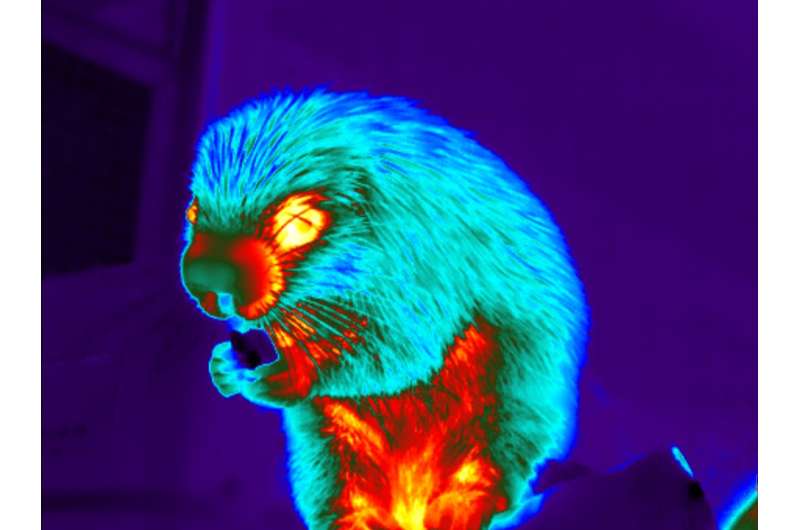

The team set out to investigate the utility of infrared thermography (IRT) coupled with Eulerian video magnification (EVM) software in measuring the vital rates of exotic wildlife species with an eye toward eventually applying the technique to studying Weddell seal populations in Antarctica in order to determine whether the animals will be physiologically prepared to survive and reproduce in a rapidly changing environment.

« Heart and respiration rates are often used as proxies for determining metabolic rate, » explained Rzucidlo. « Thermal cameras can detect changes in skin temperature associated with blood flow and changes in air temperature associated with exhalation. Thus, determining if thermal cameras could non-invasively capture these temperature changes in animals was the first step. »

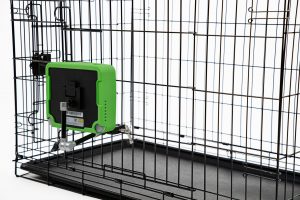

A thermal video camera can easily measure heat and body temperature, like the technology used to screen humans for fever at the airport, but could it be applied to exotic animals? Taking their work straight into the field wasn’t an option because they first needed to validate the accuracy and precision of the method, and these first steps were more suited to a controlled setting. « We had no idea how effectively we could measure temperature fluctuations with the thermal camera, including how close or far away from the animal we needed to be, and how fur, fat, or scale thickness would affect the readings, » she added.

The Cincinnati Zoo & Botanical Garden provided an ideal environment to test a range of animals under different conditions to fine-tune their methods. Working with Erin Curry, Reproductive Physiologist, and other animal care experts, Rzucidlo spent months embedded at the facility to collect thermal video on a variety of terrestrial and marine animals. Some of the work took place at other facilities, including the Louisville Zoo (Kentucky), Columbus Zoo and Aquarium (Ohio), and the Salisbury Zoo (Maryland). A total of 58 individual animals participated in the study—from Komodo dragons to polar bears.

« Being able to monitor individual animals under human care created a controlled setting to validate this technology that is impossible to replicate in the wild, » said Rzucidlo.

« Zoos offer a unique setting to develop technologies that can contribute to the conservation of wildlife populations. Animals in zoos have regular veterinary check-ups and some individuals are even trained to participate voluntarily in wellness exams, so using a stethoscope to obtain true heartrates while concurrently collecting infrared video of a variety of species was a very achievable goal, » added Curry.

The team soon learned that the thermal video alone wasn’t enough. « Capturing heat and temperature is one step, but we needed the EVM computer software to amplify changes in temperature associated with respiration rate and heartbeat, » explained Rzucidlo. « Using the two together was the winning combination and offered us an unprecedented view of animal health. »

Although thermal cameras have been used to extract vital rates in a handful of species (mostly those without hair), this is the first study to apply this technology to a wide range of exotic animals and identify what characteristics make a species a good candidate for obtaining measurements via thermal imaging.

« This new study takes thermal imaging data in a controlled setting and allows us to build benchmarks across a suite of species. Having developed and fine-tuned these methods in the zoological setting, we can then take these imaging techniques and apply it to answer much broader ecological questions in the wild, » said WHOI’s Shero.

« We’ve even been using this method in Antarctica to study energy dynamics in Weddell seal populations. We can use these newly developed methods to start asking how an animal’s energetic expenditure may change if environmental conditions change, or what the energetic demands are for reproduction. »

« What’s more, is that using non-invasive and quickly acquired imagery tools will allow us to make better measurements with less disturbance, and for a lot more animals than would ever have been possible using traditional techniques. This is what is really needed to start asking questions about population health. »

More information: Caroline L. Rzucidlo et al, Non-invasive measurements of respiration and heart rate across wildlife species using Eulerian Video Magnification of infrared thermal imagery, BMC Biology (2023). DOI: 10.1186/s12915-023-01555-9

Source : https://phys.org/news/2023-03-exploring-ways-heart-respiration-wild.html