Shapely, upright ears. Like humans, pigs have idiosyncratic faces, and new players in the Chinese pork market are taking notice, experimenting with increasingly sophisticated versions of facial recognition software for pigs.

China is the world’s largest exporter of pork, and is set to increase production next year by 9%. As the nation’s pork farms grow in scale, more farmers are turning to AI systems like facial recognition technology – known as FRT – to continuously monitor, identify, and even feed their herds.

This automated style of farming has the potential to be safer, cheaper and generally more effective: In 2018, pig farmers in China’s Guangxi province trialling FRT found that it slashed costs, cut down on breeding time, and improved welfare outcomes for the pigs themselves.

But it also has the potential to leave behind independent, small-scale farmers, who cannot afford to introduce this kind of technology to their operations.

As one Guangxi-based farmer told the Guardian, FRT just isn’t an option for many farmers.

“Farms with less than a hundred pigs, they can’t afford to track the [pigs’] faces,” he says.

FRT is able to differentiate between pigs by analysing their snouts, ears, and eyes. The system used in Guangxi farms constantly tracks pigs’ pulses and sweat rates; at the same time, voice recognition software monitors individual animals’ cough rates.

In this way, it is able to spot warning signs before a pig becomes sick or hungry. Being a “highly expressive” animal, the cameras are even capable of recognising distress in the animals’ faces.

Technological changes in China’s $70bn pork industry comes after a turbulent two years in which the country’s pig industry was devastated by outbreaks of the African swine flu.

“If they are not happy and not eating well, in some cases, you can predict whether the pig is sick,” said Jackson He, the CEO of Yingzi Technologies, which developed the software.

Yingzi is one of a handful of startups revolutionising the country’s $70bn (£52bn) pork industry. It comes after a turbulent two years that has seen China’s pig industry devastated by outbreaks of the African swine flu, leading to the death of 40% of the country’s pigs.

A more hi-tech pork industry with a smaller number of much larger firms is at the heart of the state response to the disaster.

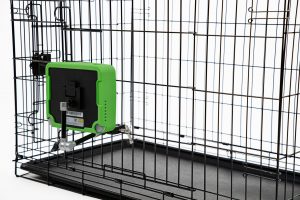

At a Yingzi farm, surveillance cameras are linked to feed dispensers – allowing the system to administer individualised feeding plans.

Farms with less than a hundred pigs, they can’t afford to track the [pigs’] faces

Farmers are also sent personalised notifications through an app, allowing them to adjust rations manually if they so choose. All this makes for a more hands-off relationship between farmer and pig – but the technology also allows farmers to be more efficient.

By tracking pigs from birth to slaughter, firms like Yingzi can build up a database of information on each animal’s growth rate. This allows farmers to cut down on wasted food by as much as 20%, with the FRT system optimising the amount of food served to each animal.

Precision livestock farming (PLF), as this sort of self-calibrating system is widely known, is helping to beef up bottom lines at farms around the country – and not simply by limiting waste. Over time, data taken from thousands of pigs has allowed Yingzi and its competitors to constantly refine these algorithms.

The right balance of nutrients, at the right stage of the growth or estrous cycle, can cut the breeding cycle down by as much as two weeks, according to one company insider, and can even improve pork quality and taste.

In a country home to more than half the world’s pigs, it’s unsurprising that the advent of FRT farming has proved a major moneymaker. Last year, Yingzi rolled out its Future Pig Farm system to hundreds of farms across southeastern China, which allowed individual farmers to cut rearing costs by anywhere from 30% to 50%, according to farmers who spoke to the Guardian.

One of Yingzhi’s biggest competitors – JingQiShen Organic Agriculture – has installed its version of FRT at more than 200 pig houses, which together are capable of producing 200,000 animals a year. Over the next three years, it hopes to have 3 million pigs covered by FRT – largely across swathes of China’s snowy northeast.

British machine learning expert Prof Mark Hansen says this new type of farming is “certainly more humane” than traditional methods. He mentions that FRT replaces the need to tag pigs’ ears with cast-iron RFID clips; it also marks a shift from reactive to proactive healthcare. Hansen describes the success of firms like Yingzi as a “win-win” for both pigs and farmers.

If they are not happy and not eating well, in some cases, you can predict whether the pig is sick

But the benefits of FRT are not likely to reach every farmer. Chen Haokai, one of the cofounders of intelligent farming startup SmartAHC, estimates that the labour cost of monitoring pigs’ faces hovers around $7 per pig – as opposed to traditional tagging, which he says costs about $0.30 per pig. Additionally, fixed installation costs such as a central database and cloud infrastructure can cost hundreds of thousands of dollars.

If these developments prove to be too expensive for small-scale farmers, it will probably further concentrate agricultural capital in the hands of just a few. In the 1980s and 90s, around 80% of pork made its way on to Chinese plates from small back yard farms – by 2018, that balance had flipped, with 80% coming from farms with 500 or more animals.

If new technologies like FRT become too expensive for small-scale farmers, only a few players will control the agricultural capital. Photograph: VCG/Getty Images

Indeed, FRT has attracted the interest of some of the country’s biggest corporations. Alibaba, Tencent, JD.com, and Netease have all opened subsidiaries and moved into the agricultural space for the first time.

Large-scale farms, backed by investment corporations interested in expanding into the agricultural sector, will probably continue to reap the rewards of these new technologies, leaving small-scale farmers struggling to compete.

Many of the biggest industrial pork producers posted record profits during the outbreak.

While it may be making pork farming both more humane and more profitable, itis unclear whether China’s headrush into this new remote, hi-tech style will benefit its rural population.

Throughout the Covid-19 pandemic, FRT firms have focused on improving on their intelligent farming technology, rather than choosing to make it more accessible; in May, Yingzi updated its 3D Pig Farming App, a remote-control VR platform which, according to CEO Jackson He, makes the management of pig farms more akin to “playing games”.

Lire la suite: www.theguardian.com