Researchers at Cornell University have been studying the forest elephant for years, trying to figure out — like Allen did with the savanna elephant — how many there are and how fast they are being killed. Given how stealthy the forest elephants are, Wrege began to think that rather than look for them, maybe he should try something a little different: Maybe he should listen for them.

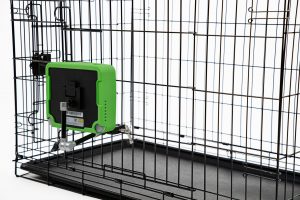

To do this, Wrege had 50 custom audio recorders made. He divided the rainforest into 25 square kilometer grids and headed to Central Africa. His team placed one recorder in every grid square about 23 to 30 feet up in the treetops, just a little higher than an elephant could reach with its trunk while standing on its hind legs. And then they hit record. Three months later, they would return to the forest, locate the recorders, change the batteries, put in new audio cards, and start all over again.

As the months wore on, the recorders were collecting hundreds of thousands of hours of jungle sounds, more than any team of graduate students could realistically listen to — which meant Wrege had another problem: How could he sort through all these recordings to find the elephant voices he wanted?

To analyze sound, a subset of artificial intelligence known as a neural network needs a visual representation of a sound wave called a spectrogram. The graphic above is a spectrogram of two elephants communicating through low-frequency rumbles. The white line is the upper boundary of infrasound, about 20 hertz, below which humans can’t hear.

Courtesy of the Elephant Listening Project

In fact, there’s a subset of AI — something called a neural network — that is very good at this. A neural network is essentially a group of algorithms, or mathematical equations, working together to cluster and classify information and find patterns humans wouldn’t necessarily see. It is particularly good at working with images, so Wrege ran the audio through a software program that turned the recordings he had collected into spectrograms — ghostly little pictures of sound waves. He then had a company in Santa Cruz, Calif., called Conservation Metrics build him a neural network that could sort through the cacophony of jungle sounds and find elephants.

But then an interesting thing happened — Wrege and his team at the Elephant Listening Project heard something else they weren’t expecting in all those recordings: gunshots.

Assuming the gunshots were a pretty good proxy for poaching attempts, Wrege decided to ask Conservation Metrics to build another neural network, this time to look for the sounds of gunshots. He hoped it would provide additional information about where the forest elephants were being killed and perhaps even stop poachers before they fired.

Lire la suite: www.npr.org