Animal care is the top priority for livestock producers, and today’s consumers share that concern as to how those animals that will ultimately end up on their dinner tables are treated.

Tami Brown-Brandl and a team of researchers at the University of Nebraska-Lincoln are creating technology that will hopefully provide that management information to the animal caretaker.

Brown-Brandl, a UNL department of biological systems engineering professor, focuses her research on precision animal management, or what some people call precision livestock farming.

“Precision animal management is really trying to find technologies that we can put within the animal environment to collect individual animal data,” she says. That data then needs to be summarized to aid producers in making management decisions. “Producers are very busy people, so we can’t just give them raw data,” she adds.

The specific research Brown-Brandl alludes to focuses on early disease detection using radio-frequency identification technology to monitor individual pig feeding behavior and track what the pig eats and drinks. A dashboard is being developed to help producers more readily identify sick animals sooner by monitoring an individual animal’s feeding behaviors in real time.

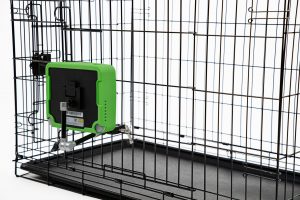

Brown-Brandl says each pig will have an RFID ear tag, and an antenna that will read the tags is attached to the feeder and by the waterer. “So, when the pig comes to eat, we know which pig is eating, and we know how long they spend eating, and what time they eat,” she says. “We can get a lot of information that we aren’t using yet.”

Flag sick pigs

The main intent of this project looks at large changes in feeding behavior. By looking at an individual pig’s eating pattern over a few days, the computer will predict how much time each pig should be spending at the feeder.

“If there is a large difference between the projected feeding time and actual time a pig spends eating, the program can send a flag, and that flag says, ‘Please go check that pig,’” Brown-Brandl says.

In addition to identifying the pigs that decrease their baseline feeder time, Brown-Brandl says the systems can also flag “slow starters,” those pigs that “after being moved to a new facility either can’t find the feeder, or if there is some other stressor that keeps them from spending at least 10 minutes a day eating.”

This technology has been installed in a facility at the USDA Meat Animal Research Center in Clay Center, Neb., for about eight years, and it can also flag animals that may be experiencing a steady decline in behavior and feeding over a long period of time. “They may be lame or have a chronic condition,” Brown-Brandl says. “Those pigs would be really hard for an animal caregiver to find in a system.”

Downsides

Despite the technology’s ability to assist caregivers in pinpointing animals that may need individualized care, Brown-Brandl admits some minuses are the cost of the system and ear tags, as well the labor of putting the RFID tags in each finishing pig’s ear.

“Animal caretakers do a great job of picking out animals that are sick,” she says, “but understand that when you go into a building, those animals don’t want to appear sick, so it’s hard to identify those animals until they’ve been sick for a few days.”

Another phase of the research places depth cameras over the drinkers, “so when the pigs come to drink, we’ll be able to capture a depth image, which gives us a projected volume of a pig. In our research, we have found that’s actually a really good indication of weight,” Brown-Brandl says.

This technology will not only determine if the animals have a large change in feeding behavior or need to be checked for illness, but also observe weight gain over time and “know precisely when each individual animal is ready to be marketed,” she says.

UNL received a grant through Merck Animal Health’s High-Quality Pork Award. On top of the $200,000 from Merck awarded last fall, the Nebraska Department of Economic Development also granted an additional $100,000 to further fund the research.

The goal of the project is to apply the technology to a commercial operation in the U.S. and evaluate its implementation in the farm setting. It also would be applied to a commercial operation outside the U.S. to understand any global implications.

“We are a global society,” Brown-Brandl she says. “I cannot guarantee we could pick up every disease. I think that ability to understand feeding behavior and how it ties to disease is critical. And that would not necessarily just be in Nebraska, or in the United States. Swine disease is a global issue, and that is why this is so important.”

Source : https://www.farmprogress.com/animal-health/technology-aids-pig-caregivers